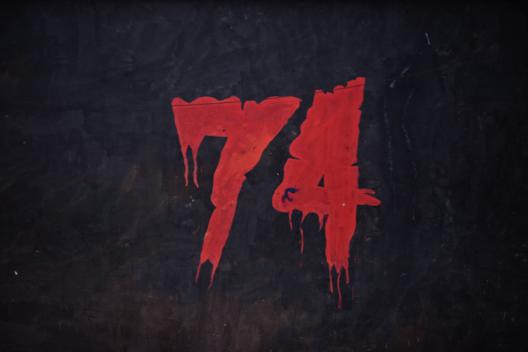

February 1, 2012, Port Said Stadium, Egypt. What began as a highly anticipated football match between rivals Al Masry and Al Ahly would end in one of the darkest days in the history of the sport. Seventy-four lives were lost. Over 500 injured. The following is a recollection of that fateful day, told through the voices of those who lived it, saw it unfold, and were forever changed by it.

🗣"The Air Felt Different"😥

Mohamed Ahmed, an Al Ahly fan, remembers the tension long before the match began. "We knew something was off. There were rumors, whispers in the stands that today wouldn’t be normal. It wasn’t just a football game anymore. It felt like war."

Two days earlier, the Ultras Green Eagles, the Al Masry fan group, had uploaded a song on YouTube. Its lyrics still haunt those who heard them: “If you come to Port Said, write to your mom a letter because you will die surely... there are no more jokes, you will seriously see death.”

Many thought it was nothing more than the usual banter between rival fans. But Mohamed wasn’t so sure. "When we heard the song, I laughed at first. But then I kept thinking about it. Why this song, why now? It felt like they were really telling us to stay away."

But Al Ahly fans never stayed away. Football was their life, their passion. On February 1st, thousands of them boarded trains from Cairo to Port Said, eager to support their team. Little did they know they would never return home the same.

🗣"We Were Trapped Like Animals"😭

Ahmed Youssef, another Al Ahly supporter, describes the chaos that followed after Al Masry's 3-1 victory. "At first, it was like any other pitch invasion. Masry fans rushed the field, celebrating, waving flags. But then something changed."

Thousands of Al Masry fans swarmed the pitch, attacking the Al Ahly supporters trapped in the stands. "We were sitting ducks," says Omar El-Sayed, another Ahly fan. "The police—they just stood there. They wouldn’t open the gates. We tried to climb over, but people were being crushed. I saw men and boys falling, suffocating. Some were stabbed."

🗣"We Were Trapped Like Animals"😭:

Ahmed Youssef, another Al Ahly supporter, describes the chaos that followed after Al Masry's 3-1 victory. "At first, it was like any other pitch invasion. Masry fans rushed the field, celebrating, waving flags. But then something changed."

Ahmed recalls seeing the first signs of danger. "I saw a guy—he must have been no older than 20—picking up a rock and throwing it at the Ahly fans. Then more people joined in. They had knives, clubs, bottles. I thought it was just some idiots, you know? But then they kept coming."

Thousands of Al Masry fans swarmed the pitch, attacking the Al Ahly supporters trapped in the stands. "We were sitting ducks," says Omar El-Sayed, another Ahly fan. "The police—they just stood there. They wouldn’t open the gates. We tried to climb over, but people were being crushed. I saw men and boys falling, suffocating. Some were stabbed."

🗣"The Police Didn’t Care. They Wanted Us to Die."👨✈️😡

One of the most damning accounts comes from Manuel José, the Al Ahly coach. José was nearly beaten to death by Masry fans as he attempted to escape the pitch. "I was hit, kicked, and punched. I couldn’t believe what I was seeing. These people weren’t fans—they were murderers."

His voice breaks as he recalls the moment that changed him forever. "The gates were locked. People were pounding on them, screaming for help. And the police—those who were supposed to protect us—sat there, doing nothing. They let it happen."

🗣"They Wanted Revenge"😤🇪🇬:

Many believe the massacre was more than just an outburst of football violence—it was a politically motivated attack. Brent Latham, a columnist for ESPN, pointed out the suspicious timing of the riot, occurring exactly one year after pro-Mubarak forces stormed Tahrir Square. "This wasn’t just about football. It was about silencing the Ultras Ahlawy, who had been at the forefront of the Egyptian revolution. The massacre was a warning."

Indeed, the Ultras Ahlawy had been a powerful force during the 2011 protests against Hosni Mubarak’s regime, often chanting revolutionary slogans at football matches. The massacre, some say, was the authorities' way of retaliating against those who had dared to challenge their power.

🗣"I Can Still Hear His Voice"😭:

In the aftermath of the massacre, the heartbreak spread beyond the stadium. Families were left shattered by the loss of their loved ones. Rania Ahmed, mother of slain fan Amr "Steef" Ahmed, recalls the last moments she shared with her son.

"Steef had the chance to leave. He could have walked away, but he stayed to help his friends. That’s the kind of person he was. He never thought of himself, always others first."

Her eyes well up as she clutches a portrait of Steef, her voice trembling. "He was 26. Just an accountant. He wasn’t supposed to die like that. The forensics said his ribs were crushed. My boy—he stayed behind to save his friends, and he paid with his life."

🗣"I Sold Everything for Him"💔💰

Mohamed Abdallah was only 21 when he died in the massacre. An engineering student, he had been engaged to his childhood friend for five years, and they were set to marry soon. His father, Ibrahim Abdallah, struggles to find words to describe the emptiness his son’s death has left behind.

"I sold everything I had to buy him an apartment. Everything was for him. And now… all I have left is this room." His voice breaks as he looks around at the photos and mementos that once filled Mohamed's space with hope and promise. "I can still see him here, you know? But he’s not coming back. They took him from us."

🗣"This is a Black Day for Football"⚽️:

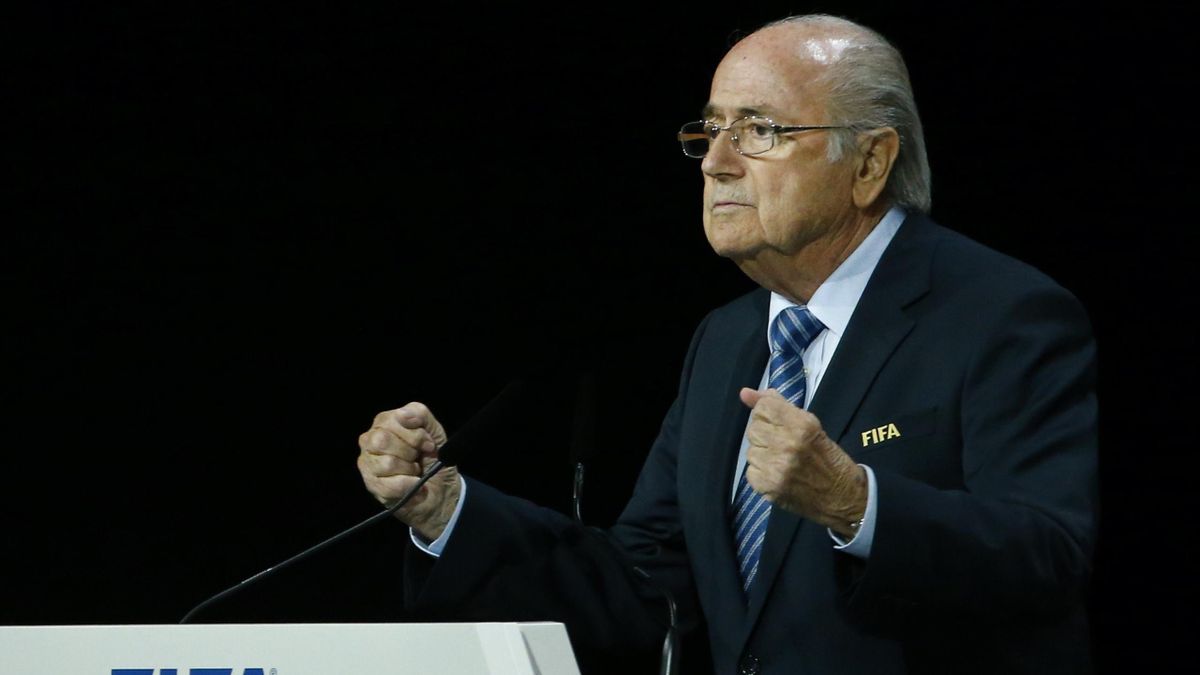

The international football community was stunned by the events in Port Said. FIFA President Sepp Blatter released a statement calling it "a black day for football." He added, "Such a catastrophic situation is unimaginable and should never happen."

But for the families of the victims, these words offered little solace. The Court of Cassation eventually convicted 47 individuals for their involvement in the massacre, including 11 death sentences. But for many, the damage was already done. Egypt’s domestic league was suspended for two years, and the national team suffered as a result.

🗣"We Must Never Forget"🇪🇬❤️

It has been years since the Port Said Stadium massacre, but for those who were there, the memories remain fresh. Survivors like Ahmed Youssef still struggle with the trauma of that day. "Every time I go to a football match, I can feel it. I can hear the screams, see the bodies. I don’t think I’ll ever truly escape it."

Manuel José eventually left Egypt, but the scars remain. "I loved that country, I loved that team. But what I saw that day—it changed me. Football should never cost lives."

For the families of those lost, every year brings a new wave of grief, but also a renewed determination to keep the memory of their loved ones alive. As Rania Ahmed says, "I will never forget my Steef. And neither should the world. This is not how football should be remembered. We must never forget."

_large.png)